JADRANKA'S FIRST LIFE, EXHIBITION BY BOŽENA KONČIĆ BADURINA

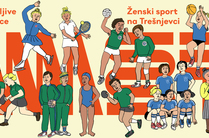

JADRANKA'S FIRST LIFE, exhibition by Božena Končić Badurina, inspired by the life of Trešnjevka born Jadranka Klekar, women's and workers' rights activist.

Nova BAZA, Nova cesta 66

March 21 — April 16, 2023

Working hours: Tue — Fri: 4 — 8 p.m., Sat — Sun: 11 a.m. — 3 p.m.

*on Tuesdays exhibition is open until 6 p.m.

Jadranka, female given name, derivative from the male name Jadran + suffix - ka (very common; 12 818 women named Jadranka)

In the 1950s this name was the ninth most common name in Croatia, given mostly in Istria, the Croatian Littoral, and Dalmatia. It was also popular in the 1960s, particularly in the Croatian Littoral, and Zagreb and its surroundings.

Who is Jadranka whose first life is the subject of this exhibition? I search famous Jadrankas and fast results confirm the statistic: the majority of them were born in the period between the end of the World War II and the 1970s. It seems that the popularity of the name Jadranka is related to the period of socialism, calling to mind other popular names from that time: numerous women named Nada, Željka, Zdravka (Hope, Desire, Healthy in English), etc. But what else does the name Jadranka imply? It is a dedication to the blue Adriatic (Jadran in Croatian), our sea that continentals long for, imagining heaven as its most beautiful bays (perhaps even blue lagoons). Again, the statistic confirms it: Jadrankas were born not only near the Adriatic Sea, but in the Zagreb area, as well. One such Jadranka is the one we are looking for: born in Zagreb in 1954, Jadranka Klekar.

***

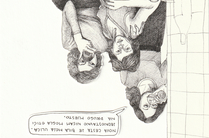

Not knowing where it would take us, in 2021 we invited artist Božena Končić Badurina to explore the virtual collection of the Trešnjevka Neighborhood Museum (continuously in the making). Soon Božena started coming to the meetings carrying a black cover notebook, whose white pages started filling with different characters: a pastry baker, a cook, a waiter, a flower saleswoman, a doctor; sometimes followed by a handwritten personal name. And then August Cesarec appeared, a Croatian writer, an intellectual, a cultural worker, and a communist, born in 1883, killed in 1941. He was the shadow editor of the Voice of Trešnjevka gazette, which gave voice to Trešnjevka’s workers in the interwar period. Real workers’ lives served as an inspiration for protagonists of Cesarec’s short stories with unhappy endings, whose plot and resolution were a consequence of social inequality and systemic repression of those who were trying to earn their daily bread. One such bread was of particular interest to Božena, which resulted in the workshop titled "Mountains of Bread, Pretzels of Mud’" after a scene from a Cesarec’s short story, led by Božena and writer Olja Savićević Ivančević. The following year the workshop turned into the art and literature workshop titled "Paper that heals: paper collage and words", conceived as healing sessions in which contemporary workers’ lives were combined in collages with those preserved in the Neighborhood Museum collection. In the first workshop meeting we did an exercise of collective storytelling about a black and white photograph from the Collection: a young woman sitting at the flower kiosk. After we completed our fictional story, we found out the facts: the young woman was Jadranka Klekar, 16 years old at the time, in her first job at the Trešnjevka Farmer’s Market.

***

While we were reading together Cesarec's short stories (The Wreckage of the Rožman family, Tonka's only love, Octopus, and others), our conversations, as well as Božena's black notebook, filled with working class apartments, rooms without a toilet that were home to entire families of Cesarec's wretches, rooms with communal courtyards, overseen by landlords or their hirelings collecting rent that grew every month. Many of these huts are still there, even in close proximity to the New Baza Gallery. A lot of them have been torn down, but new apartments, with bathrooms, toilets, even kitchens, brought along new landlords – rents and loans are chains that make us relate to Cesarec’s protagonists.

***

In a conversation during the preparation of the exhibition, Jadranka Klekar mentioned the song Daddy, buy me a car as a song that marked her childhood. That says a lot: the hit written by Ivo Robić is a commonplace motif in conversations about Yugoslavia and an opportune entrance to a discussion on its specific socialism, which saw market relations being integrated already at the end of 1950s. It is a song of abundance and consumerism for a society that, only 15 years before, was wrapped up in misery, which, of course, was nowhere near to being completely eradicated, despite large modernization steps and enviable growth that resulted from the impetus of the socialist project. Leftist theorists of the political economy of Yugoslavia, such as Darko Suvin or Micheal Lebowitz, discuss the tension between the market and the planning approach, and how introducing the market by the side door gradually undermined the socialist project, in the end resulting in unemployment, lack of public resources, economic crises, and an increase in social class inequality. This brings us to some other songs that could be heard in the 1980s, such as the one about young Bosnian men from the bottom of the class hierarchy who, while some are walking on the moon, cannot even go to the seaside. Our heritage from socialist Yugoslavia is both Ivo Robić and Zabranjeno pušenje (No smoking, the Yugoslav band from the 1980s whose lyrics we refer to), in other words, the results of contradictory efforts. On the one hand, this involved reduced social class differences, working class apartments, which for some workers finally meant running water, power, air, light, and space, widely available education, public health, and other public resources that we become more aware of, the more they are endangered under capitalism. On the other, it implied a society which was divided by class in the decade preceding the bloody war, in which working class women always remained under the line on apartment allocation lists, left to dwell under conditions worthy of Cesarec's protagonists.

***

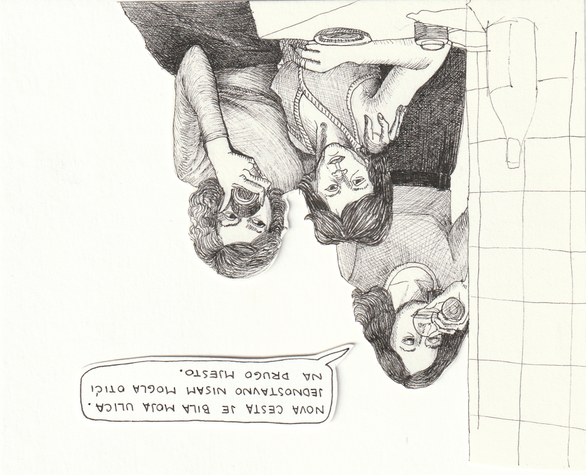

The exhibition presents Jadranka's first life through several fragmented sequences that entail addresses, spaces, dates, scenes (in a detailed drawing, mostly based on the photographs), first-person and third-person narration, in a neutral radio speaker’s voice. At certain moments, it seems like the fragments could belong to another Jadranka, another worker. Through one life we see other lives, micro-histories of the Trešnjevka micro-location, typologies of working class apartments in Nova Cesta and nearby streets, the chronology of the Laguna hotel. The hotel holds a particularly important place in Jadranka’s (first) life: in sharp contrast with the harshness of her apartments (rooms) without running water, it appears to be almost a utopian collective home, where life unfolds – from feeding and bathing, to working, socializing and taking care of children. Its name, Laguna (The Lagoon), and the fact that it was founded as a Zagreb subsidiary of the Blue Lagoon in Poreč, is another Adriatic motif in this story. In the last episode of Jadranka’s first life, Laguna is the place where her struggle, which she has been engaged in throughout her life, became collective in 2001 when, joined by other workers, she called a strike, today practically forgotten. Jadranka’s first life thus represents a somewhat unconventional excerpt from history, which does not end with 1990s and the breakup of one state and the establishment of another, but rather meanders through a turbulent transitional period, and in between lines implies long processes, a perspective that is more complex, but also more complete than the simplified narratives of the disintegration.

***

Jadranka's first life puzzled me for a while: is she a tragic character or a heroine of her own battles? Only when I permitted myself to interpret her personal story within the broader context, did I start noticing elements in it that had nothing in common with the symptoms of a tragedy typical of Cesarec. She was able to get educated, her workplace offered her safety, replacing home in a way, she felt she was earning well for the most part of her working life, she could afford things, she was an independent woman who managed quite well without a man, and she raised a child by herself. When we asked her if there was anything she would have done differently in her life, her answer was no. She told us they called her to come to Poreč and work for Blue Lagoon; she did not want it because she could not leave her grandmother, who was rather elderly at the time. The question is, what her life would look like if she had left, and what the struggle of the Trešnjevka’s Laguna workers would look like in that scenario. Jadranka did not want to go to the seaside, she was emancipated enough to continue her Trešnjevka struggle, along those few streets, and primarily in Nova Cesta, where the artistic representation of her first life is taking place. Jadranka’s story in a way symbolizes a broader story about our society and its numerous workers who lived with contradictions of Yugoslav socialism, and all this is happening a small venue on her Nova Cesta. On this occasion, this venue embraces other spaces, eight nearby locations in Trešnjevka to be exact, as well as the ninth, imaginary: her ideal apartment which remains an object of struggle in a life that follows, and which is above all others in the central spatial installation. Above it, there are only clouds, white waves of Jadranka’s utopian lagoon.

Ana Kutleša

Božena Končić Badurina (born in 1967) graduated in Russian and German Language and Literature from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, and from the Academy of Fine Arts, Graphic Arts Department. She regularly exhibits alone and participates in group exhibitions, at relevant events and eminent institutions both at home and abroad. She bases her work on research, often having an interest in stories of women in different social contexts. Her recent production includes the following works: "If the Factory Honked" for the Siva Zona (Gray Area) Gallery, Korčula and Miroslav Kraljević Gallery (GMK), Zagreb, produced in 2020, "Equality, Fraternity, Liberty: Where Are You?" for the Industrial Art Biennial in Labin, 2018 (curatorial collective WHW), "Here and There" for the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMSU), Rijeka, 2017, "Adžijina St 11 User Manual" for BLOK, 2016, and "Ćemo, ćemo… ja, ma kako ćemo?", MMSU, Rijeka, 2017.

Jadranka Klekar (born in 1954) is a human rights activist, who advocates especially for the rights of women and female workers, She was born in a working-class family (her father was an auto mechanic, and her mother was a housewife), as the middle child of three children. She started working for the Laguna Hotel when it opened in 1973, and stayed there until 2008, working in different positions, simultaneously obtaining education in hotel industry. In 2001, as a trade union representative, she organized a strike of the hotel staff, after which she continued with activities of workers’ union organizing, completing a number of informal trainings in the area of human, women's, and workers' rights. She has lived in Trešnjevka all her life.

Author: Božena Končić Badurina

Curator: Ana Kutleša

Collaborator: Jadranka Klekar

Exhibition Design: Ana Dana Beroš

Construction: Ana Dana Beroš, William Linn, Nikola Brlek

Sound Design: Dalibor Piskrec

Speakers: Anamarija Štorga, Dražen Puklavec

Support in Materials: IR - GO Ltd.

The exhibition is part of the "Trešnjevka Neighborhood Museum – Living Heritage" program. It is financially supported by the Ministry of Culture and Media of the republic of Croatia and the City of Zagreb, City Office for Culture, Intercity, and International Cooperation and Civil Society. BAZA’s annual program is supported by the "Kultura Nova" Foundation.