THE ART OF THE COLLECTIVE: CASE ZEMLJA

19 November 2018 – 15 January 2019

KRSTO HEGEDUŠIĆ GALLERY, MATIJE GUPCA 2, PETRINJA

February next year marks the ninetieth anniversary of the founding of the Artists Association Zemlja (Earth), a socially engaged group of painters, sculptors and architects. Despite the fact that almost a century has passed since their time, their collective work and their attempts to answer the question of what is the art of the Left, art created collectively and intended for the collective, their questions remain relevant to our times. We do not wish to recreate a historical example in a contemporary situation as if it were a recipe, in fact our goal is to historize the art practice of Zemlja. In order to do so, we inspect the broader socio-political context of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the inter-war period: the period of economic crisis and capitalism’s intense outspread, the prohibition of labour organization and progressive political action under the dictatorship of the Karađorđević dynasty, and the time of impending fascism. The period is ‘staged’ in gallery space through an abundance of archival materials and interpretations of the neuralgic issues of the then Yugoslav society – the questions of peasantry and nation – that are unambiguously reflected in the art of the Artists Association Zemlja.

The historization of ‘Case Zemlja’ also imposes an issue previously neglected in the narratives about Zemlja, that of the association members’ ties with the social movements of the time. We highlight the association’s relationship with the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. At the time, the Party still operated under complex and illegal conditions, and was weighed down by internal, factional conflicts. As a legal form of action, art often took over the role of political propaganda. The artists’ understanding of the social function of their practice is showcased through their interviews and autobiographies, as well as records of police hearings. These documents reveal that the artists had their knives out for the heteronomous criticism of the autonomy of art in the society at the time, but that it also caused conflicts and disagreements both within the association itself and in the broader art field. In this way, the exhibition revives the key points of conflict on the literary left, resisting simplifications and simple interpretations of the ways in which it reflects on the art of Zemlja.

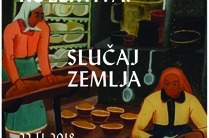

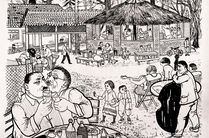

The problematization of art as an autonomous activity is best illustrated in Zemlja’s relationship with the proletariat, whether it be artistic (and political) work in the Croatian countryside, independent trade unions or the suburbs of Zagreb, where day labourers and landless peasantry went to seek their fortune in their masses. Archival materials are accompanied by artwork across the spectrum of techniques – from lace and tempera on glass to prints and oil on canvas – with motifs of bereaved women whose cattle are being seized, police repression of the rural poor and good-for-nothings, hard everyday life of peasants, as well as the misery of workers’ slums. For the first time in decades we also present Krsto Hegedušić’s paradigmatic painting with the motif of the unsuccessful uprising of the ‘green cadres’ who, to borrow Krleža, acted in vain and with no politically integral forces. The ‘female side’ of Zemlja isn’t overlooked and comes in the shape of the rarely exhibited lace work of the group’s sole woman with full membership, Branka Hegedušić, as well as the representation of women’s work and exploitation – from reproductive labour to difficult physical work in the fields and industrial labour. The interdependence of rural and urban areas at the time of introducing capitalist production relations is clearly revealed in Stjepan Planić’s posters, taken from the ‘Village’ section of Zemlja’s fifth exhibition, as well as Marijan Detoni’s graphics, which illustrate life and work in the mud of Zagreb slums.

In these works, the members of Zemlja accurately portray class antagonisms that are immanent to capitalist society. Therefore, the issue of collectivist art – as the members termed their practice, emphasizing their opposition to the individual position of a bourgeois artist representing the class interests of exploiters – is just as relevant today.